Siemens has been in business since the days of the electric telegraph when it was founded in 1847. A critical factor in its longevity has been its ability to adapt to evolving technology, which continues today with artificial intelligence (AI), software and sustainability taking centre stage.

To get a glimpse into the past, present and future of the German conglomerate, Sustainable Biz Canada toured the headquarters of its Canadian subsidiary in Oakville, Ont. Called its "living lab," the company is testing a variety of software and hardware, much of it geared toward improving energy efficiency, reducing waste and shrinking carbon emissions.

Mindful of climate change and the fourth Industrial Revolution, Siemens is orienting its business to address sustainability and technologies that allow “industry to do more with less,” according to Faisal Kazi, president and CEO of Siemens Canada.

“From a perspective of doing the right things, really addressing the challenges which humanity’s facing and to be part of the solution, has been absolutely very exciting,” he explained. “And it has a business case.”

Building X

When entering the Siemens Canada head office, a grey-skinned android named Evo greets staff and visitors. Standing upright in the lobby, Siemens staff attempted to demonstrate the ChatGPT-powered robot, which can answer questions about the company.

Evo was shy initially, unresponsive to the first inquiry. “I never saw this,” one Siemens employee murmured about Evo’s momentary malfunction. After a reboot, however, Evo was wide awake as if roused from a deep nap, accurately replying to a question about who was visiting the office on that day.

The lineage from a pointer telegraph (which is in the building) to Evo is indicative of Siemens’ history and flexibility. It is a global company that operates in the infrastructure, mobility, health care, software and financial services sectors, with a sustainability angle often present.

One example is Building X. In a room furnished with electric vehicle chargers, a vacuum circuit breaker and a switch gear, digital success manager Enass Badawi showcased the software platform.

Building X draws from a network of sensors in a building, collecting data on metrics such as occupancy, temperature and energy use. “It puts the client in control and it gives them data to make a decision,” she said.

An energy manager tool in the platform allows building owners to track the performance of an asset and create an energy budget per building or across the portfolio. Using AI and machine learning, it can set an energy consumption baseline for a building and monitor patterns in its systems.

If a system deviates from the norm, it will trigger an alert.

The sustainability manager of Building X tracks the energy consumption and carbon emissions, and highlights the best and worst performing buildings. The building owner can develop a decarbonization plan and track progress toward energy and carbon targets with the tool.

Building X can reduce a building’s carbon dioxide emissions by approximately 30 per cent compared to its baseline, Siemens says.

Digital twins, AI design, edge computing

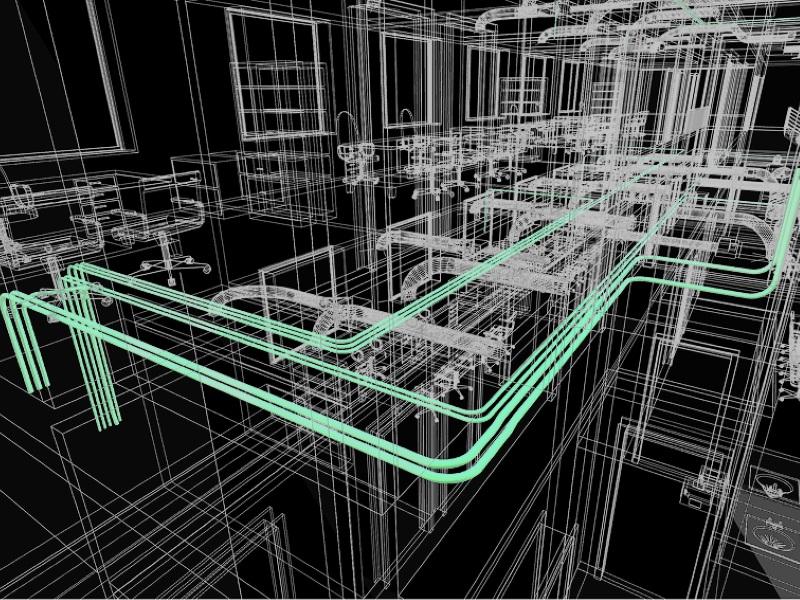

In another room called the Xcelerator Lab, Siemens is testing its digital twin technology – a virtual replica of physical equipment or a system based on real-world data. The asset can be designed, built and validated digitally, then interacted with in virtual reality, akin to a video game.

If engineers want to make changes to a prototype, it can be done digitally without needing to spend money, time, resources and effort on the physical asset.

Siemens' 73,000-square-foot factory in Nanjing, China was designed using the company's digital twin technology. Compared to a similar factory without a digital twin, it runs 30 per cent more efficiently and is 20 per cent more productive, Kazi said.

“This is great example to show how you could solve real-world problems in the virtual world.”

In another example of how digital solutions intersect with sustainability, Kazi noted the use of generative AI to design equipment.

Siemens let an AI program design the gripper of a robot arm, only setting baselines such as the purpose of the part to guide its decisions. A few minutes later, it produced a gripper that weighs 80 per cent less compared to one drawn up by a human.

That translates to approximately 90 per cent less carbon emissions per gripper, Kazi said. The gripper, which was first tested virtually, worked well when it was recreated in the real world, he continued.

Higher productivity, better competitiveness

The technologies Siemens is developing will “help increase the productivity of Canadian companies,” Kazi said. “When they are more productive, they are more competitive.”

But an energy-intensive technology like AI, which underpins much of Siemens' innovation, could offset some the efficiency gains.

Recognizing the possibility, Kazi is keeping a close eye on the edge computing space. Rather than process information in large data centres, he hopes it could be computed closer to where the data is being generated, reducing energy consumption.

Advancements in edge computing could be a “game changer” for the sustainability implications of AI, Kazi said.